By Peter Cole. [After their first stint on the President Coolidge, Peter and the team spent the following year doing salvage work at Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands, then on the Hatsuyuki at Bougainville in PNG and later in the Western Solomons. The Onewa was lost off Vanikoro and replaced with the Pacific Seal an ex Australian diving tender, 66 feet long with a forward wheelhouse and a large aft working deck. It was powered by an old American diesel engine; a Hercules DNX six cylinder. John Lindsay, a New Zealander (nick-named Fang because of his voracious appetite) and three islanders from the Shortland Islands joined the team in the Solomons.]

Back in Sydney in early 1972, I caught up with my mates and scrounged a mattress on the floor in their flat. We were back drinking at the Cremorne Strata, just like I hadn’t even been away. A couple of mates had got married and one moved to Brisbane. I didn’t have a steady girlfriend at that time, but still kept in touch with all the girls I knew.

Later, I caught up with Barry (Barry May). He was busy opening a new dive shop in Balmain, and I spent a few days giving him a hand fitting it out.

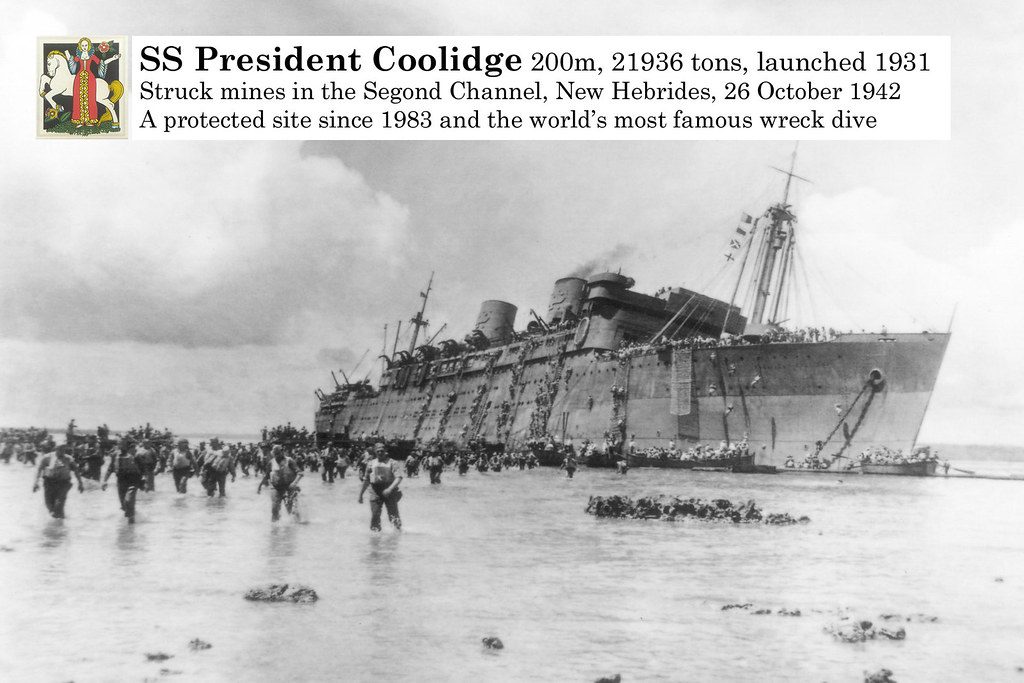

One evening Barry and I were having a beer, and he started telling me his plans for the President Coolidge. He wanted to get into the engine room where there was a lot of scrap. The engines were turbine-electric; steam turbines to drive generators, which drove the electric motors attached to the propellers. All of it full of heavy copper windings. In each boiler room, there was a large condenser, full of brass and bronze, plus all the associated pipework and cabling. In short it was an Aladdin’s cave for a ‘scrappie’. But, like Aladdin’s cave, there were serious problems to get in. First there was the depth – 140 to 170 feet – we would need a decompression chamber, a high pressure air compressor, better diving equipment. All our equipment was considered antique now. Then there was the problem to remove the hull plating to expose the engines and boilers. But the problem to top everything was the bunker oil; Barry estimated there was about 500 tons still in the tanks. (Later another salvage company recovered 800 tons!). It would have to be removed and stored or disposed of before any serious assault on the engine room could be attempted. Another problem was that the Pacific Seal was getting a bit long in the tooth, and all the equipment was getting old too. Barry said he was having talks with the New Hebrides Government regarding removing the oil, but they were not exactly falling over themselves to offer any serious incentive to proceed. The other negative aspect of the whole operation was the price of scrap copper was falling. A big mine in Chile had started producing again meaning the demand for copper was being met by producers, and scrap copper was taking a steady decline.

But, he still wanted to carry on. Number 1 Hold hadn’t been opened yet, and he was keen to see what was inside. And there was still a massive amount of ammo in Number 3 Hold waiting to be dredged out. We would continue with that while he negotiated with the New Hebrides Government. But we would need another diver. TC (Barry Tween Cain) was out of diving now; he and Bill (Bill Martin) were leaving salvage and going into transport. I told him I might have the answer to that – my mate Keith Nolan was interested – and it would be better to have someone we knew rather than a stranger. He agreed. So later that evening I told Keith about it. He was a bit hesitant at first because he had never dived, but I told him he would soon pick it up. We got him a wetsuit from Barry’s shop – they made them there – and some diving gear and after two weeks we flew up to Honiara to bring the Pacific Seal down to Santo.

Barry had radioed us to say that he couldn’t make it to Honiara and we would have to find a competent skipper/navigator to do the trip down to Santo. So I asked my friend Phillip Palmer, who was in Honiara, if he could do it. Of course he could! Well, that’s settled then.

Three days later (after veering more than 40 degrees off course), at daybreak we reach and enter the Seagond Channel and pass the poor old Coolidge laying under the surface. We then move on to the small ships’ wharf, where our scrapyard was. We have been gone almost a year, but nothing has changed! That’s Santo.

The first thing we need, after clearing into the New Hebrides, is transport. I call Barry on the radio and let him know we have arrived at Santo, and he okay’s a vehicle; preferably a pickup or utility.

I go and see the local Toyota agent, a Frenchman called Jean Desplat. Bill purchased the Toyota utility from him last year. All he has in our price range is an elderly Peugeot 403 pickup. He says it’s been serviced and is running well, so I buy it. Burns Philp, the big trading store, is the agent for these cars and holds plenty of spare parts; they are a popular vehicle.

Philip flew back to Honiara after a few days and we decided to go and visit the Coolidge. Barry suggested we start pulling out the degaussing cables as a start. These cables are strung the length of the ship, on either side. With a suitable current passing through them, they will neutralise the ships natural magnetic field. The point of this is to avoid setting off magnetic mines. The cables are about as thick as an arm, rubber insulated, with a thick copper core.

The method of recovering the cables, when I look back on it, was insane, but at the time it was just a normal procedure. We would take down a nylon sling and the winch cable, find an open porthole in the hull – they were nearly all open when the ship sank – and drop the winch hook inside. With a hacksaw attached to our weight belt we would then wriggle inside, find the cable overhead and attach the sling and hook it up to the ship’s cable. We would then signal to the winch driver to take up the slack, so the hook and nylon sling were on the outside.

By this time we had stirred up so much silt that you couldn’t see a thing, so everything from then on was by feel. We would pull in enough hose and tie it off, then feel our way along the cable until we reached the bulkhead. With the hacksaw we would start to cut through the cables – there were two of them. As they were cut they crashed down into the hull, so we had to make sure our hose was clear. When both were cut, we had to find our way to the porthole by following our hose, then feel our way to the other end of the cable and cut it too! Now we were swimming in a thick Pea Soup with only our hose to guide us out. Once out, we would signal the winch driver to pull, and slowly the whole length of cable would be pulled out.

It was so dangerous. With only one person in the hull we had no back up hose or bottles. If the falling cable had caught the hose, we would be dead in seconds. There was no escape route and you couldn’t see your hand in front of your mask. But we happily crawled inside the coffin and literally cheated death every time!!

We could only reach the starboard side, so once we had cleaned out all the cables, we cut them up into manageable lengths, and took them ashore to burn off the rubber insulation. Then we put them into a drum and thumped it all down. The drums were heavy when full!

About this time a friend of ours from Sydney arrived at our boat out of the blue. We were sitting on the back deck, and Keith said “Hey, that’s Ray.” pointing to a guy walking into view. Sure enough Ray Heath ambled across the wharf and climbed onboard. He said he had come up for a holiday, but we found out later that he had just completed a diving course in Sydney and wanted some ‘commercial diving experience’. He was heading back to England and wanted to get into the diving game!! Fair enough, he could do some dredging, in Number 3 Hold.

The weather had turned quite choppy; too uncomfortable to work on the Coolidge, so we decided to find the USS Tucker, which was at the southern end of the Channel. Fang had been there before so we set off; it wasn’t far away.

The USS Tucker was another American ship that committed suicide by running into one of its own mines. It appeared to be a common practice! It was a destroyer, built in 1936 and sank in 1942. It broke in two and sank in 80 foot of water. It had been extensively worked by other salvors, but it was a nice easy dive and there should still be some scrap to be found. Indeed it was an easy dive; clear visibility and a nice sandy bottom. We scavenged around the engine room area and managed to fill a few drums with mostly copper pipe.

After a couple of days we returned to the Coolidge. The weather had calmed down so it was back to work.

One dive, Fang and I were at Number 3 Hold. Fang was inside picking up large shells, passing them out to me, and I was dumping them into the basket. Suddenly there was a loud roar, and everything started shaking; debris was falling down everywhere inside the hold. I instantly knew it was an earthquake, and tugged Fang’s hose. He appeared out of the murk, and I’ll never forget the look on his face; a cross between amazement and terror! I think more terror! He scrambled out and we held onto the basket. I signalled for them to pull us up, and we rode up to the surface hanging onto the basket. After a short deco stop we climbed aboard. They were still talking about it!!

They all thought someone had started the main engine! The Seal rattled and shook. We told them what it was like underwater and in the hold; the noise was incredible, somehow amplified by the water. Fang said all the shells had started shaking and plumes of silt were shooting up from the pile. He said it was like a giant was pushing from underneath!!! That was enough diving for the day; no one wanted to go back down!

One Monday morning before we left the wharf, Fang took the ute into town to buy some fresh bread. Town was about two kilometres away so it should only take 15 minutes to go and come back. Two hours later he turns up in another car driven by another person! So the obvious question was, “What happened?”

His answer made us laugh. He was driving along when acrid smoke started pouring into the cab. He pulled up and popped open the bonnet, and the engine bay was on fire. So he ran into the nearest shop – Chinese – and shouted, “Fire, Fire”. The Chinaman ran outside, saw the flaming car, ran back inside and grabbed a fire extinguisher, and put it out. Fang pulled the battery terminals off, and they stood looking at it. “What happen?” asked the Chinaman. Fang shrugged his shoulders, “I don’t know.” “You go, Toyota, They help” said the Chinaman, pointing down the road (he didn’t speak very good English).

So Fang walked back to the Toyota Agent, but it was too early and nobody was there, so he had to wait until Jean Desplat, the owner, turned up half an hour later. He told him what had happened. Jean told him to go back and wait; that he’ll come along when his mechanic turns up. Another half hour wait, and the mechanic turns up. They had to push the ute around so it was facing back, and he towed it back to the workshop. It looked a mess, so Jean said he would have to leave it there. Fang asked the mechanic to drop him back to the wharf, and here he was!

“So, where’s the bread?”

“Oh, S***, I forgot the bread!”

We didn’t bother trying again, we dropped the moorings and headed for the Coolidge. The car was ready on Friday. The battery cable had arced out and melted all the insulation which then caught fire. It had to be rewired. These were the daily trials we had to endure, which, I guess, is the same the world over!

[In July/August 1972 Peter spent six weeks in Sydney.]

After my stay in Sydney, I flew back to Santo to continue working on the Coolidge. Although I was happy to be back, I didn’t really enjoy diving any more.

While I was in Sydney, Keith had bought a Suzuki 90 road scrambler, so he could be more independent. The Suzuki agency in Santo was owned by the father of a French diving friend of ours, Jan, and he had just imported two TS 185 motorbikes which he had sitting in the showroom. I couldn’t resist it and bought one.

I carried on diving for a few more weeks, before having a major scare. Keith and I were in Number 1 Hold that Barry had blown open while I was away. They had recovered large artillery shells and a huge pile of perfectly preserved tyres, most of them still on rusted spare wheels. These were sold locally, as there were still plenty of vehicles in use that the tyres fitted. There were hundreds of cases of Springfield rifles, and more shells behind these cartons. Keith and I were going to clear a space so we could get to the shells.

I went in first and pulled in my hose and tied it off; this stops it trying to float to the surface and pulling you with it. Keith was pulling his hose in but it had snagged on the edge of the hold. Instead of swimming up to it to release it, he gave it a big jerk. The sharp edge of the rusted steel sliced into his hose and he lost all his air!!

The next thing I knew he grabbed my regulator out of my mouth and put it into his. Now I was out of air, so I grabbed it back. In a few seconds we were both only ten seconds from death. I took a deep breath and let him take the regulator back. Then I unhooked my hose harness, left him with the regulator, and swam out of the hold. I dropped my weight belt and finned it up to the surface as fast as I could.

I was at 90 feet with only a lung full of air, and I was taking care to let it dribble out of my mouth as I ascended; necessary because compressed air will expand in your lungs as the pressure lessens. I could see the boat’s hull on the surface and aimed for the boarding ladder. I broke surface just next to the ladder and scrambled aboard. Fang and the crew looked stunned.

“I need a bottle” I yelled, “Keith’s got no air.”

Fang pointed to a bottle with a regulator attached, laying on the hatch “Full?” I asked, picking it up, he nodded. I leapt back into the water with the bottle under my arm and peddled down as fast as I could. I was terrified I would find Keith dead, it was an awful feeling. I swam into the hold, and there he was, alive!!! He was trying to untangle his hose and untie mine. I grabbed hold of him, and he gave me the thumbs up. Once untangled we both ascended at a steady rate. Back on board, he told me that once I had left, he was getting enough air from my hose, and when he had calmed down a bit he started to untie the hose so he could get out. It was a nerve wracking episode. We were both in 90 foot of water, inside the wreck, and probably only ten seconds away from certain death. I could really do without this!! Incidentally, I never did find out to this day, why there was an air bottle with a regulator attached, laying on the hatch!! I can never recall it happening before!

Shortly after this episode, after we had cleared out the big shells in the forward hold, Barry called us together and told us he was going to have to suspend operations, the price of scrap had fallen to an all-time low, and everything was getting progressively more expensive. It was just not profitable anymore. And the N.H. Government would not, or could not, come to the party with a viable plan to remove the bunker oil from the wreck. This was about mid-August 1972. Barry left for Sydney, and Keith followed a few days later.

Barry had told us to find a skipper and take the boat to Vila and lay it up. We decided to take it down ourselves. We could do the trip in two daylight runs, with an overnight stop at Port Sandwich. We would be island hopping all the way.

After we had cleaned up and packed everything away we set sail. It was an easy run, and we arrived at Port Sandwich in the afternoon. No one on board had been there before, but the chart showed a safe anchorage and a small wharf, so we laid alongside the wharf. Ten minutes later a battered old Land Rover pulled up and an European climbed out, big straw hat and a ragged safari suit.

Now what? I thought. Then he took off his hat and said “Hello Peter”. I was surprised, but suddenly I recognised Claude Chirot, the manager of Mao’s Bar when I stayed there!! He had a plantation here and recognised our boat! So he came down to see what we were up to. We chatted for a while, then he left. What a pleasant surprise.

Early next morning we left for Vila and arrived in the afternoon and tied to the small ships wharf. Over the next few days we met up with Bill and TC, tied the Seal up, stern to, on Iririki Island, and cleaned up. Then Fang left for Honiara. I was on my own, although I still had the three Shortland boys. That evening I met with Bill at the Rossi Hotel. He was with another guy, who I had met very briefly before. This was Bob Paul; a fascinating man, who had been in the Hebrides since 1947. He had a plantation on Tanna Island, and he had founded the local airline Air Melanesiae.

As the evening progressed Bill asked me what I was going to do next. I said I didn’t know; probably go back to Sydney. Bob asked me if I had any building experience. I said yes, some. He told me he had just hired a young American lad to build a new bathroom/kitchen/cyclone shelter at his house on Tanna. They were looking for someone else to help him, would I be interested? I could hardly believe my ears, Yes, I would be very interested! So we arranged to meet the other guy, Ken Rasua, who turned out to be a decent sort of chap, with a very strong American accent.

Bill wanted to take the three Shortland boys, but Masilino wanted to go back home, so we arranged his flight. The other two moved onto Bill’s ship, the Neptune. I had to leave my Suzuki at the airline office at Vila airstrip. Bob said he would fly it down to Tanna when space was available.

Ken wanted to know where I bought the bike, he was keen to buy one too. I told him Santo, and there could be another one there. So with the help of Bob and Burns Philp, they got in touch with Jan’s dad, who said he had just imported another two. Ken paid for one, and Jan’s dad arranged to ship it to Vila. Complicated! But that’s how it worked in those days. Just about all communication was through a radio network; satellite phones were still thirty odd years away!!

A few days later Ken and I flew down to Tanna in a noisy Britten Norman Islander!

Copyright Peter Cole 2023. All rights reserved.