By Peter Cole. [In 1970, Peter was working with two co-workers in a non-ferrous scrap metal yard in Mascot, Sydney.]

One day the boss said that they were expecting a shipment of scrap from the Pacific Islands, we were all intrigued. Eventually a large low loader backed in with about one hundred drums of scrap on board. We spent the rest of the afternoon unloading and stacking them.

The owners of the scrap were two Aussie salvage divers , Barry May and Des Woodley, and they accumulated all this scrap from the island of Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides, (now known as Vanuatu).

The scrap arrived on Friday, and as we did not work on the weekend, the boss told them they would have to wait until Monday before we could start sorting. Well, they did not want to wait, so they asked if anyone wanted to work over the weekend and they would pay them. I volunteered, the other two declined, so I was on my own. But that did not matter, I knew how to sort and I already had a key to the yard, I was always first in to open up during the week.

So, Saturday morning, with Barry and Des, and another guy they brought with them, we set to.

The other guy’s job was to open the drums. Typically the drums had the lid cut out and the drums were filled with scrap. When full, the lid was placed on top of the scrap and the edges hammered over to secure the contents. Opening them was harder than closing, I was glad that was not my job. Then, when open, all the contents were tipped onto the floor and we started sorting.

To get some idea of how we did it: the metal we mostly dealt with was copper, bronze, brass, aluminium and nickel silver to a lesser extent. Copper came in several grades; number one bright, tarnished and corroded, soldered fittings or attached to iron or steel. Bronze, came in valves, flanges, bits of machinery. Brass came in taps, valves, plumbing fittings and shell and bullet casings. Domestic copper came in vehicle radiators, gas heaters, kettles, pots and such like, copper wire, clean and bright, burnt wire and insulated wire, and on a smaller scale cupro nickel, or nickel silver as in cutlery etc. And of course aluminium pots and pans, lead pipe and old batteries.

As we were sorting I was pointing all this out to Barry and Des, who knew the basic differences, but I was showing them how to sort for the best possible price; pre-sorted and graded scrap fetched much better prices.

By Sunday afternoon we had everything sorted, weighed and stacked. So on Monday morning the boss had a quick check and was more than satisfied with our efforts, and so were Barry and Des, who got many thousands of dollars more than they expected.

That afternoon they both came back to the yard and gave me $200. I was elated, that was a month’s wage at the time!! Then they closed in on me.

Barry said “Look Pete, we need someone like you sorting in our yard in Santo” – a quick look to make sure the boss was not around – and Des chimed in, “Would you like to come and work for us?”,

WOULD I ?, Damned right I would!! So Barry gave me his address in Mosman, and told me to come around and they would discuss it all, and that, as they say, is how I ended up in the New Hebrides.

As it turned out, Barry and Des had just been joined by two other guys who were also salvors, and had their own salvage boat. They used to be in opposition, but had now joined forces to share the spoils. There was a lot of scrap in New Hebrides, Solomon Islands and PNG, and it made sense to work together – that was Barry, the diplomat. Bill Martin and Barry Tween Cain (TC for short) were the other two. I met TC later, and Bill when I arrived in Santo.

On the 6th of June 1970, I flew up to Noumea, New Caledonia, with a friend of TC, who was going up for a holiday. There was no direct flights to Port Vila at that time, so it was a stopover in Noumea. The only airline flying that way was UTA, the old French airline, and the plane was an elderly French built Caravelle. I found out later it was on its eleventh year “extended airworthiness”. Yikes!!

We overnighted in an hotel in Noumea, and next morning clambered into an even older Douglas DC 4, and we rattled our way to Port Vila, the capital of New Hebrides.

We landed on a grass strip, and the ‘terminal’ was an open ended tin shed; a bit like a tractor shed on a farm. Our passports were stamped – no visa, work permit or residency needed, just turn up!!

Later on we took the same plane to Santo, and landed on an old US bomber strip up in the hills.

We were met by TC, who drove us to the hotel where his friend was staying. He was on holiday. I was staying on the work boat, I was NOT on holiday. Here I met Bill Martin for the first time. Bill was a carton a day man, and I rarely saw him without a can of Fosters in his hand or close by, but he was a great guy, we got on well.

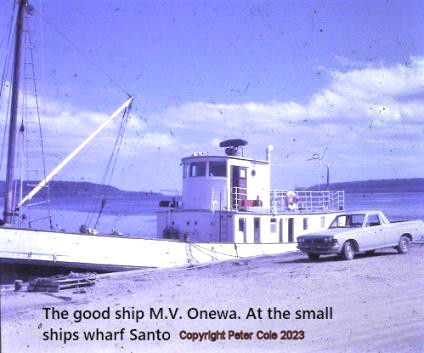

The workboat was called the Onewa, it was 70 foot long and built in New Zealand some 50 years earlier. It was powered by a Gardiner 8L3 diesel engine of unknown vintage!! The hull was quite narrow with extra-large sponsons to accommodate a wider deck. She was originally designed to run the bars and shallow waters of New Zealand’s west coast; up here she was in semi- retirement!

My first job was to sort out all the accumulated scrap. The yard was a large concrete slab where an American Quonset hut had stood during the war. The hut had been recently removed by a local Frenchman, but the slab was ours. The scrap was corralled by a ring of drums, it was a huge pile, so I got started, in the blazing tropical humidity!!

After a week, Bill and TC were satisfied I could handle the job and so I was moved into an outside room at the beachfront hotel called Mao’s Bar. Now, don’t get carried away here, it was a hotel in name only. It was actually an assortment of jerry built buildings, around a central hall which housed the bar, dining room, dance floor, small stage and kitchen. Just about every type of building material had been used in its construction; brick, blocks, timber, lumps of coral, roofing iron… You name it, it was there. But it was (sort of) clean and tidy, and the ‘beach’ was a rocky coral area in front of the hotel which ran down to the Seagond Channel. My room was at the end of a block of four – concrete block walls, iron roof, and a toilet and shower inside, which I appreciated.

The owner was a Tahitian called Mao. I don’t know if it was his first or last name, because I never actually met him, he had just left for Tahiti a few weeks earlier. The place was being run by a manager called Claude Chirot. Claude was rotund, somewhat 60 and a Pacific Island Frenchman. He was a friendly guy and started teaching me French, although he spoke good English. Just simple stuff, and I always got a smile or “Bravo” when I attempted to speak French. I think he may have been Mao’s in-law, because his wife was Tahitian too.

I hadn’t been there long when one night I was suddenly shaken awake, but there was nobody in the room. I could hear things falling on the floor, and I jumped out of bed, only to be thrown against the wall. “What the hell”!! Then I realised it must be an earthquake. I could hear people shouting and a woman screaming. This was quite a big shake. I made it to the door and got outside; other guests were emerging. Then suddenly, it stopped and went eerily quiet. Claude came out and told everybody to move on to the beach, just in case there was another one. We all stood around for a while, but all was quiet, so people started drifting back to their rooms. Claude gave me a big grin, “Merde!” he said, and wandered off.

Des had hired a couple of locals to help in the yard. They were Mark, a young man, and Old Bill. I have no idea why he hired Old Bill as he was at least 60 in the shade and he didn’t do much work. But that was Des!! Every morning they would turn up and Old Bill would greet us with “morning Masta”; this was a throwback from the old colonial days when all white men were called ‘Master’. I found it a bit disconcerting at first. Des had told him a dozen times not to use that title, but Old Bill just ignored him. I soon got used to it, and just ignored it too. The younger generation didn’t use that term but most of the older men still did.

After I had settled in, Bill and TC took the Onewa down to Port Vila. They were starting a bit of a refit by installing some new water tanks. They were going to use about ten 44 gallon wine drums, these were lined with a potable plastic lining, and were used to ship wine from France. Also Bill’s wife was coming up and TC had a Vietnamese girlfriend in Vila too, so good enough reason to go. I was left in Santo.

It was at this time that I got to know Alan Power, and his wife Delphine. Alan, or AP, as he was known to us, was a photographer and diver, he had published a book about the sea life on the Great Barrier Reef, and he was a keen and competent underwater photographer. He had come up on the Pacific Seal with Barry and Des and was one of the team that salvaged the props of the President Coolidge. After that job he decided to stay in Santo, rather than go back to Sydney. He was renting half of a residential Quonset hut in town. He had his own diving gear and compressor, but no transport, while I had a Toyota ute. So I used to pick him up in the morning, and bring him and his dive gear to the small ships wharf, where we had our yard. He would set up on the corner of the wharf and jump in. The water was mostly quite clear and he would take photos of marine life or look for scrap for his own collection.

One day he asked me if I would like a go, diving that is…,

“Hell yes”, I was dying to have a go.

He had a spare mask and regulator. “Just breathe normally,” was the only instruction I got. It was amazing to be able to breathe under water, and to see clearly – it didn’t take long before I was swimming around like a fish. We used to move about the wharf and slowly searched the whole length. I used to fossick around for anything interesting; I found old Coke bottles, a rusty helmet, all sorts of pipe, some copper, some brass, shell casings, and odd and ends. AP took photos, and searched for scrap. There was a lot of stuff laying close to the wharf.

One Saturday morning I was strolling through the local market in town, just looking and enjoying the atmosphere, when I spotted a strange sight; an old man was sitting on a box, next to his produce, smoking a homemade pipe. What was strange was his head; it was long and pointed, and looked a bit alien. I couldn’t help staring. He looked at me and gave me a smile. I came out of my trance, smiled back and ambled on.

When I told AP and Delphine, they told me that it was Head Binding or Artificial Cranial Deformation; the practice of binding a baby’s head with the intention of elongating the skull. Apparently it was quite common on Malakula Island before the Europeans arrived, but the practice was banned now. This old boy was probably one of the last of his kind.

Talking of Malakula Island; it is the second largest island in NH, and had a fearsome reputation for fighting and cannibalism. It is inhabited by two tribes, the Big Nambas, who live in the hills and the Small Nambas, who live on the coast. The ‘big’ and ‘small’ titles had nothing to do with the size of the people, but described the size of their Penis Sheath, which was the traditional attire in those days. The last known event of cannibalism on this island was 1969, a year before I arrived!!! The story goes, that the son of a Big Namba chief was getting married, and the chief wanted to give his son a traditional feast, so he sent a war party down to the coast, where they killed a couple of Small Nambas, and carried them up to the village and ‘they’ were the traditional feast!!! When word got out, the French, in a knee jerk reaction, sent a Mirage Bomber from New Caledonia and bombed the Big Nambas village!!! I don’t know if this really happened, but it was a common story when I was up there, and everyone I asked affirmed it was true. Claude, who lived on Malakula, said yes, they did bomb the village! Knowing the French, I think it must have happened!!

After about six weeks the Onewa returned. I had sorted and weighed about 40 drums of scrap and this was enough for a shipment to Sydney, which proceeded forthwith. We took all the drums to the main wharf and Bill arranged shipment on the Messageries Maritimes vessel Le Caledonien, which was due into Santo soon.

After Bill and TC got paid, they had enough money to fit a new auxiliary engine which would hydraulically drive the anchor winch and cargo winch, and also to install a decent compressor. All the equipment was ordered from Sydney and was due to land in Vila soon, so they decided to close the operation in Santo for a while and move back to Port Vila for the refit. I moved out of the hotel and on to the Onewa. I was now a permanent member of the crew and with a Fijian skipper, Tom, and one local deckhand, we loaded the Toyota onto the deck and sailed down to Port Vila.

Copyright Peter Cole 2023. All rights reserved.